StartupCities

StartupCities

Who?

Who?I'm a software engineer and entrepreneur focused on modern web technologies and AI.

Here's an ongoing autobiography, which also shares the story of my by-the-bootstraps "unschooling" education: now the subject of a chapter on grit and resilience in the bestselling book Mindshift by Barbara Oakley.

An angel investor once described my core soft skill in the role of founder or early team member as: "The ability to perceive exactly what needs to be done. And then to do it."

My experience working in difficult environments around the world means that I can be trusted to get things done, even when things go wrong.

In the past, I coined the term "Startup Cities" as co-founder of StartupCities.org and a startup spinoff, both of which focused on why startups should build cities. I now write about Startup Cities at StartupCities.com

I've won several awards for economic research and have been published or interviewed in Virgin Entrepreneur, a16z's Future.com, The Atlantic's CityLab, Foreign Policy, and in academic volumes by Routledge and Palgrave MacMillan.

Wait... what is this site?

This is my personal portfolio, inspired by the question: "What would the opposite of the two-color template developer blog look like?"

Have fun exploring!

Click the Start Menu to learn more.

Contact:hello @ zach.dev

Inventing - How the Masters Did It

On self-education, mafias, and side-projects in the history of invention

Part biographical sketches, part pattern-matching on the psychology and process of great 19th century inventors like George Westinghouse & Alfred Nobel.

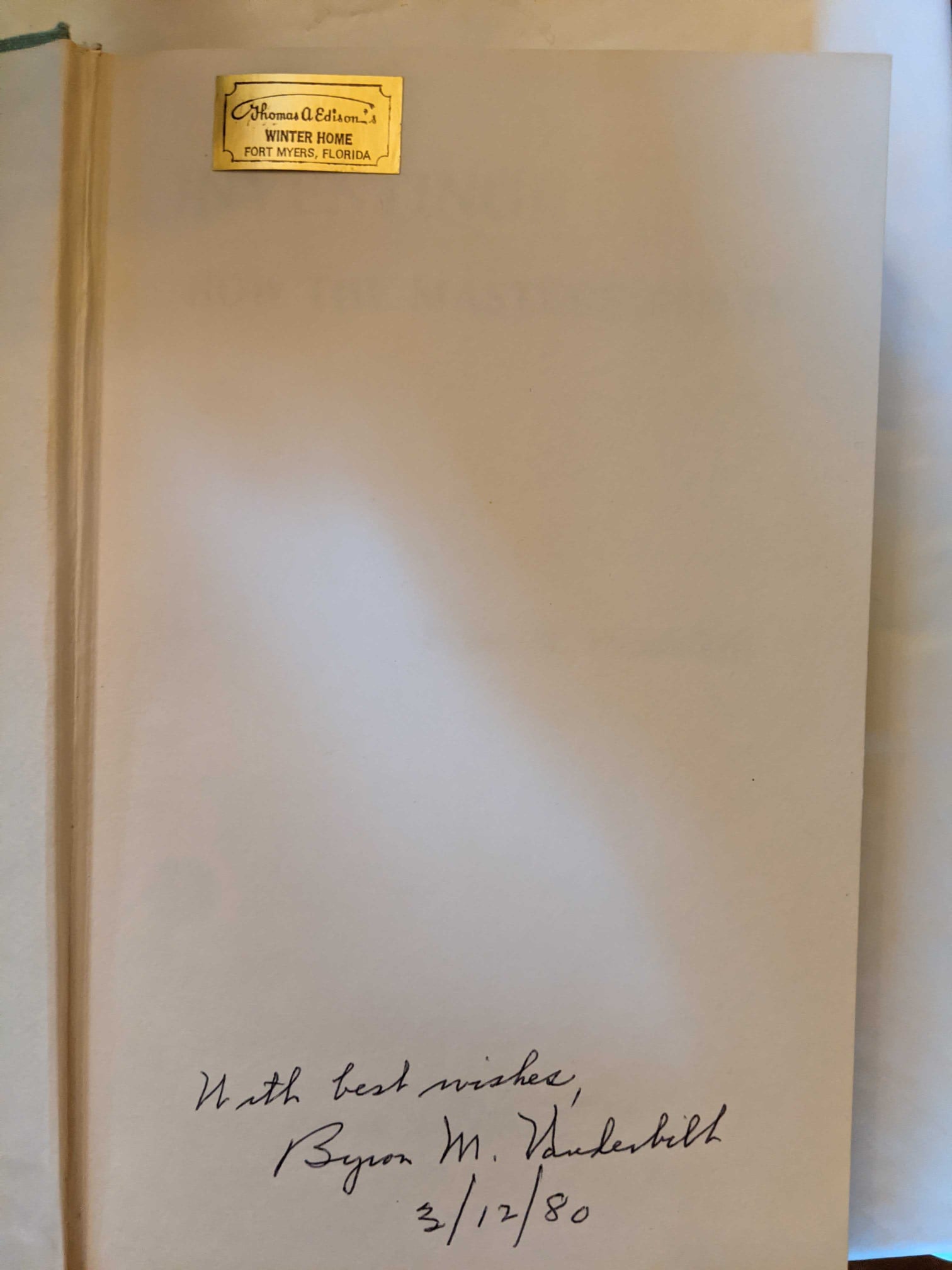

A beautiful old copy bound in green. Autographed by author and previously belonged to the library of Thomas Edison's Florida house.

It is striking that all of these greats were largely self-educated. Some barely made it to school at all due to poverty and disease. Only Bell had any college -- a few courses taken sporadically. Nobel had tutors but even he received only a "rudimentary" classical education.

This pattern holds beyond the names on this list. Charles Kettering (Delco, freon, electric starting motor) didn't graduate college till 28 after his early schooling was interrupted by eyesight problems. Elihu Thompson (696 patents) was 100% scientifically self-educated.

All showed mechanical aptitude and intelligence, but none were "child prodigies". The author suggests only Edison could be thought of as possibly prodigious, but we can't be certain because "he did not attend school".

As was typical in the era, they all began working at a young age. At 17, Nobel was sent abroad to purchase machinery for the family business. At 15, Acheson was designing machines for real use in quarries. Westinghouse worked full days in his father's machine shop by age 10.

This no doubt sounds crazy by modern standards. But each of them absorbed the habits of a tinkering engineer by starting early. Their technical education was on-the-job. And during their early employment some began work on inventions that would change the course of history.

The in-between moments -- nights and weekends -- were critical to invention. Bell taught deaf students during the day. Edward Acheson used Edison's workshop after hours. Chester Carlson (inventor of what became Xerox) worked as a patent lawyer and invented in the evenings.

Inventors largely self-financed their invention using cheap prototypes, cheap equipment, and unused space and materials. Once they had traction, they sought out what might be considered angel investors: successful merchants and bankers who wanted to support further invention.

The in-between spaces of home and work were the laboratories of invention. Bell famously used the attic of a boarding house. Acheson used Edison's machine shop at night while an employee. A factory foreman gave Westinghouse some space in a workroom for his early work.

A small-time shopkeeper named Charles Williams rented informal workspace to a young Tom Edison. Later he rented to another eccentric young man with interest in audio: Alexander Bell.

After deadly explosions, Stockholm's government forbid Nobel to continue to work with nitroglycerin. So Alfred Nobel went all Seasteading on the problem and built "an ark on pontoons" on a lake's shore. When farmers with pitchforks arrived he moved the ark to lake's center.

These inventors had mafia dynamics, supporting and competing at different times. A young Acheson audaciously introduced himself directly to the established Edison -- and got the job. Westinghouse proposed a joint venture to Edison, who snubbed him as an electricity dilettante.

Westinghouse later brought alternating current to market to compete with Edison. He also bought patents on insulated wire from a former Edison employee: Edward Acheson.

Edison also employed an immigrant from Croatia with some creative ideas about electricity: Nikola Tesla. After Edison's company refused him a pay raise, Tesla (a college dropout) turned to Westinghouse for support.

When asked about a proposed monopoly, Edison made clear that competition matters: "If you make the coalition [monopoly], my usefulness as an inventor is gone. My services wouldn't be worth a penny. I can only invent under powerful incentives. No competition means no invention."

All showed almost inhuman tenacity in the face of problems. As Edison put it:

"Spilt milk doesn't interest me. I have spilt lots of it, and while I have always felt it for a few days, it is quickly forgotten and I turn again to the future."

On the multi-decade road to vulcanize rubber, Charles Goodyear did multiple stints in debtors prison -- promptly returning to his work upon release.

"Although he had lost thousands of dollars in his private ventures, obtained several worthless patents both in the United States and abroad, and spent years of time unproductively, Acheson still had great faith in his own inventive ability."

Many will no doubt say that today is different. We've plucked the low-hanging fruit! Invention now requires expensive equipment, specialized knowledge, advanced degrees, and careful supervision. Invention belongs in the university and the corporate lab, not the attic and garage!

But I'm not so sure. How much might we be losing in the "developed world" by delaying adulthood later and later? By expanding school in hours per day and in years of life? By removing teenagers from the workforce through law and cultural norms?

If we fill up every moment of childhood with planned activities will we keep a future Westinghouse from the self-directed tinkering that leads to invention?

Or maybe none of that matters and the modern world is just too distracting for serious invention. Edwin Land (Polaroid) put it plainly:

"Interruption is bad; it is hard to get going again."

Westinghouse named his home Solitude.

Focus matters but is hard to find. One can't help but feel grateful for past invention.

Much of life today is amazing and we live off the largesse of people like Goodyear rotting in debtor's prison while on his way to deliver an invention like rubber.