StartupCities

StartupCities

Who?

Who?I'm a software engineer and entrepreneur focused on modern web technologies and AI.

Here's an ongoing autobiography, which also shares the story of my by-the-bootstraps "unschooling" education: now the subject of a chapter on grit and resilience in the bestselling book Mindshift by Barbara Oakley.

An angel investor once described my core soft skill in the role of founder or early team member as: "The ability to perceive exactly what needs to be done. And then to do it."

My experience working in difficult environments around the world means that I can be trusted to get things done, even when things go wrong.

In the past, I coined the term "Startup Cities" as co-founder of StartupCities.org and a startup spinoff, both of which focused on why startups should build cities. I now write about Startup Cities at StartupCities.com

I've won several awards for economic research and have been published or interviewed in Virgin Entrepreneur, a16z's Future.com, The Atlantic's CityLab, Foreign Policy, and in academic volumes by Routledge and Palgrave MacMillan.

Wait... what is this site?

This is my personal portfolio, inspired by the question: "What would the opposite of the two-color template developer blog look like?"

Have fun exploring!

Click the Start Menu to learn more.

Contact:hello @ zach.dev

The Tragedy of the Present

A Review of "Where is My Flying Car?" by J. Storrs Hall

Where Is My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall plays a tune on repeat. Throughout the book, Hall asserts possible futures. Some sound unbelievable: nanotechnology that could re-build the U.S. capital stock in a week, affordable and safe flying cars, an average household income of $200,000 a year. But Hall is no unhinged futurist. He justifies these futures with the obsessive, hard-nosed analysis that only a first-rate mind can provide.

Each chapter, Hall sweeps you up. He takes you to the root of nuclear power or robot housekeepers or autogyros. And, once you're won to his vision of a better tomorrow, he'll conclude: "It is a possibility." And it is. Flying Car expands a sense of the possible.

Hall argues that radically new technologies support one another. Nanotechnology, which for Hall should first resemble a machine shop that can replicate itself at smaller and smaller levels, would support the development of better nuclear reactors. After all, it's easier to play with atoms when your tools are the right size. Nuclear (fission, but eventually fusion) and geothermal ("the fission reactor at the center of the earth") blasting energy "too cheap to meter" would revolutionize flying cars.

Flying cars, in turn, would revolutionize how we build cities ("the largest technology we make"). Residents of such cities might live in a mile-high skyscraper with apartments cleaned by AI-powered robo-housekeepers. This is heady stuff. And technology as an intricate, evolving web shines through. But alongside Hall's optimism lurks a tragic story.

Robo-housekeepers and flying cars conjure up the optimism of an earlier time: the dreams of Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein, of "The Jetsons" and Syd Mead sketches. Most people assume these futurists of yesteryear were naive. These were the grand projections of an era drunk on post-war optimism. Not so, says Hall. The futurism of our grandparents wasn't impossible. We killed it.

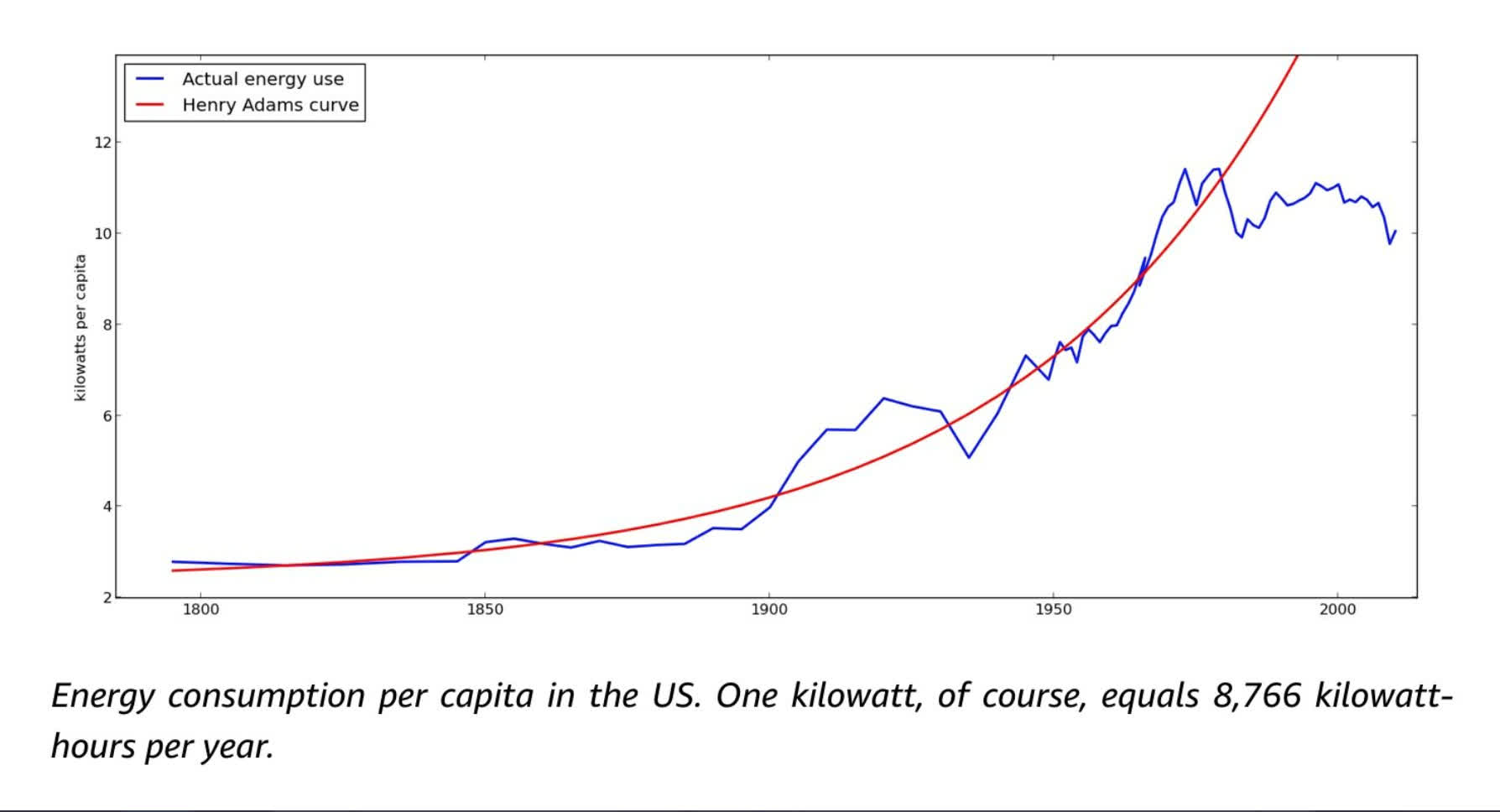

Hall reconstructs the crime scene. He joins the ranks of other analysts by arguing that something dark happened in the early 70's. The first clue is the Henry Adams Curve:

This curve describes the steady increase in energy production and use that defines the years that follow the Industrial Revolution. It flatlines around 1970. Instead of moving humanity's energy production from fossil fuels to nuclear power — a growing trend at that time — the rise of aggressive environmental ideologies and (mostly unfounded) fears of mushroom-cloud catastrophe stalled nuclear progress. Governments set widespread bans and heavy regulatory burdens.

Aggressive "Green" ideology combined with nuclear fears to create a condition that Hall calls "ergophobia": the fear of energy. Ergophobia, which treats energy use as mankind's Original Sin, means we've missed decades of progress.

Hall points to an overlooked area to show where nuclear may have been by now. The U.S. Navy continued to develop nuclear power while the Department of Energy made it hard for everyone else. Today, "the Navy has over 6,000 reactor-years of accident-free operation," Hall notes, "It has built 526 reactor cores (for comparison, there are 99 civilian power reactors in the U.S.), with 86 nuclear-powered vessels in current use" (165).

The Henry Adams Curve flatline points to a deeper set of problems from the early 1970s. Hall proves contrarian even here. He rejects Tyler Cowen's popular "we plucked the low hanging fruit" thesis from The Great Stagnation. We didn't pick the low-hanging fruit, says Hall, we sprayed the trees with plant-killer.

I've always found Cowen's argument unpersuasive. Technology is an evolutionary system that grows through recombination: we put modules of technology together in new ways. Each new innovation can itself be combined with the existing stock of innovations. This means that the space of possible technologies doesn't contract as humans invent, it expands. Rather than plucking the low-hanging fruit, technology's advance plants new trees and grows new branches.

In a world where technology grows and human desires know no limit — Hall covers this well in his section on the "Jevon's Paradox" (144) — how is it possible to pick all the fruit? Hall proposes an alternative to Cowen's stagnation thesis: a "Great Strangulation".

Several forces conspired to strangle the future and flatline Henry Adams. First, American culture became more risk averse and indulgent. In Hall's reasoning, the very success of markets and technology led to the rise of a neurotic class of ungrateful busybodies that he terms the "Eloi Agonistes".

I laughed out loud when I read this. Anyone who works in technology has met the Eloi Agonistes. This distinctly modern class often lives absurdly comfortable lives. They probably received an excellent education. They have scaled Maslow's Hierarchy. From the peak of Maslow's marvelous mountain, they survey reality. And they find it wanting.

The incredible abundance of the modern world has led these people not to happiness, but to existential despair. Hall offers a chart that shows the rise of the term "crisis" in popular culture — all while the world achieved astonishing levels of health and happiness. I'm reminded of a time where I stood in the lavish cafeteria at Google's Manhattan offices. In front of me, an engineer (who probably earns more than $250,000 a year, plus benefits) loudly groaned that today's free, unlimited, luxurious sushi selection didn't include his favorite roll.

If you follow AI research, you'll certainly meet some Eloi Agonistes. Hall, who spent decades as an AI researcher, takes on today's critics. "We want robots instead of people in positions of trust and responsibility", argues Hall (206). This is a deeply contrarian view.

There's a growing consensus that AI is inherently worse than humans and must be purged from important domains like medicine and public policy — usually to avoid bias. Hall takes the sane perspective that both AI and humans are imperfect... in different ways.

We can't assume that a human decision maker (also rife with prejudice, psychological biases, limited memory, and more) is definitely superior to an AI. But Hall avoids the hyperbole of "the Singularity". He argues that AI will first find success in narrow, practical domains. It has.

Eventually, technologists will be able to create machines that more closely approximate how a human "understands" rather than the narrow statistical pattern-recognition of today's neural networks. (For a good read on AI's possible transition from "induction " to more human-like "abduction", check out this book or the work of Melanie Mitchell).

For Hall, AI is a foundational technology like nanotech or nuclear/geothermal energy. It has massive implications for the cost and quality of our lives. Someday, Hall writes, we may be treated by "a doctor with encyclopedic expertise, instant built-in access to all the latest research, and an effective IQ of 200" (206).

The modern regulatory state is also to blame for the Great Strangulation, says Hall. By mid-century the inertia of bureaucracy came to demand more power and discretion over technology's growth. Then the Eloi Agonistes captured these bureaucracies. From the safety of their offices — bearing little of the cost or hassle of their choices — they indulged their risk-averse ideology to grow enormous regulatory burdens and bans. They assuage their agony at the future's expense.

Hall explores this regulatory argument in the context of flying cars. To my surprise, flying cars have been possible since the 1930's. Hall treats the reader to many photos of these early flying cars (all brilliantly colorized by Stripe Press). But a variety of factors such as liability laws and FAA rules conspired to destroy the personal aviation industry (186-187).

A third pillar of Hall's argument surprised me. Hall rejects the government funding of science (83). I've always waffled on this point (is the crowding out effect that big?). Hall makes a persuasive case that crowding out private investment is an important but lesser problem. The real issue is how centralized funding politicizes science.

Centralized funding leads science to what Hall calls "The Machiavelli Effect". Scientists must struggle in a zero-sum battle to control the machinery of scientific funding. "Once so much money, power, and prestige is involved, the game changes from true science to politics", writes Hall (72). Once in charge of the funding machinery, scientific partisans starve some branches of research for other, more fashionable branches.

In this criticism, Hall harkens to another great volume from Stripe Press's lineup: Scientific Freedom: The Elixir of Civilization by Donald Braben*.* Braben argues that peer review — almost a sacred idea for science — is at odds with scientific advancement. Braben makes clear that peer review of results is fine. But we can't demand that pioneers satisfy peer review to receive funding. By definition, a pioneering idea breaks with peer consensus.

My own father was involved with Stanford Research Institute's "remote viewing" research to train "psychic soldiers" in the 1960s. This is crackpot stuff. But it reveals the open-mindedness of the pre-1970's establishment, even (or especially) in agencies like (D)ARPA and the DoD. (Here I should mention yet a third Stripe Press volume, The Dream Machine, about J.C.R. Licklider's seminal contributions to technology through his work at ARPA). But the Machiavellis took charge. And, as both Braben and Hall persuasively argue, they helped impoverish the future.

In the end, Flying Car isn't about the future. It's about the tragic present. Some reviewers accuse Hall of "angry old man" vibes. I disagree. Hall strikes me as a builder. Ask anyone who has tried to build something truly new: a startup, a groundbreaking technology, a new art form, whatever. We've all had to endure the baseless whinging of the Eloi Agonistes. We've met the Machiavellian ideologues and the ergophobes and the endless critics who lack both nerve and imagination.

Hall seems like someone who has contended with the cold-blooded strangling of innovation that defines post-1970's America. He knows the future we lost — what the present could have been. Flying Car is not the railing of someone past their time, but of someone who glimpsed the future and who understands, all too well, the tragedy of the present.

Check out Where Is My Flying Car from Stripe Press.